When starting with new clients, finding the low-hanging fruit of Web performance is often the simplest thing that can be done. By recommending a few simple configuration changes, these early stage clients can often reap substantial Web performance improvement gains.

The harder problem is that it is hard for organizations to build on these early wins and create an ongoing culture of Web performance improvement. Stripping away the simple fixes often exposes deeper, more base problems that may not have anything to do with technology. In some cases, there is no Web performance improvement process simply because of the pressure and resource constraints that are faced.

In other cases, a deeper, more profound distrust between the IT and Business sides of the organization leads to a culture of conflict, a culture where it is almost impossible to help a company evolve and develop more advanced ways of examining the Web performance improvement process.

I have written on how Business and IT appear, on the surface, to be a mutually exclusive dichotomy in my review of Andy King’s Website Optimization. But this dichotomy only exists in those organizations where conflict between business and technology goals dominate the conversation. In an organization with more advanced Web performance improvement processes, there is a shared belief that all business units share the same goal.

So how can a company without a culture of Web performance improvement develop one?

What can an organization crushed between limited resources and demanding clients do to make sure that every aspect of their Web presence performs in an optimal way?

How can an organization where the lack of transparency and the open distrust between groups evolve to adopt an open and mutually agreed upon performance improvement process? Experience has shown me that a strong culture of Web performance improvement is built on three pillars: Targets, Measurements, and Involvement.

Targets

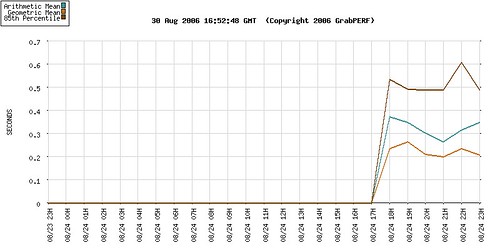

Setting a Web performance improvement target is the easiest part of the process to implement. it is almost ironic that it is also the part of the process that is the most often ignored.

Any Web performance improvement process must start with a target. It is the target that defines the success of the initiative at the end of all of the effort and work.

If a Web performance improvement process does not have a target, then the process should be immediately halted. Without a target, there is no way to gauge how effective the project has been, and there is no way to measure success.

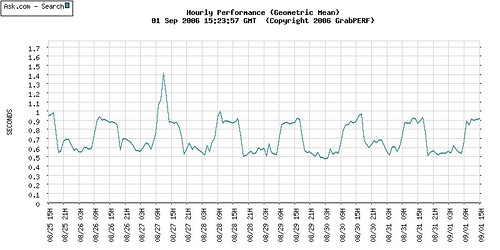

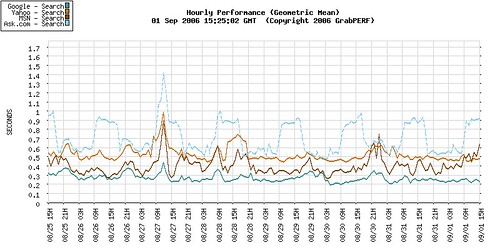

Measurements

Key to achieving any target is the ability to measure the success in achieving the target. However, before success can be measured, how to measure success must be determined. There must be clear definitions on what will be measured, how, from where, and why the measurement is important.

Defining how success will be measured ensures transparency throughout the improvement process. Allowing anyone who is involved or interested in the process to see the progress being made makes it easier to get people excited and involved in the performance improvement process.

Involvement

This is the component of the Web performance improvement process that companies have the greatest difficulty with. One of the great themes that defines the Web performance industry is the openly hostile relationships between IT and Business that exist within so many organizations. The desire to develop and ingrain a culture of Web performance improvement is lost in the turf battles between IT and Business.

If this energy could be channeled into proactive activity, the Web performance improvement process would be seen as beneficial to both IT and Business. But what this means is that there must be greater openness to involve the two parts of the organization in any Web performance improvement initiative.

Involving as many people as is relevant requires that all parts of the organization agree on how improvement will be measured, and what defines a successful Web performance improvement initiative.

Summary

Targets, Measurements, and Involvement are critical to Web performance initiatives. The highly technical nature of a Web site and the complexities of the business that this technology supports should push companies to find the simplest performance improvement process that they can. What most often occurs, however, is that these three simple process management ideas are quickly overwhelmed by time pressures, client demands, resource constraints, and internecine corporate warfare.