In the last article in this series, the concept of baselining your measurements was discussed. This is vital, in order for you and your organization to be able to identify the particular performance patterns associated with your site.

In the last article in this series, the concept of baselining your measurements was discussed. This is vital, in order for you and your organization to be able to identify the particular performance patterns associated with your site.

Now that’s under control, you’re done, right?

Not a chance. Remember that your site is not the only Web site your customers visit. So, how are you doing against all of those other sites?

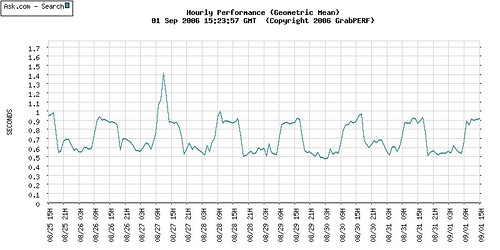

Let’s take a simple example of the performance for one week for one of the search firms. This is simply an example; I am just too lazy to change the names to protect the innocent.

Doesn’t look too bad. An easily understood pattern of slower performance during peak business hours appears in the data, presenting a predictable pattern which would serve as a great baseline for any firm. However, this baseline lacks context. If anyone tries to use a graph like this, the next question you should ask is “So what?”.

What makes a graph like this interesting but useless? That’s easy: A baseline graph is only the first step in the information process. A graph of your performance tells you how your site is doing. There is, however, no indication of whether this performance trend is good or bad.

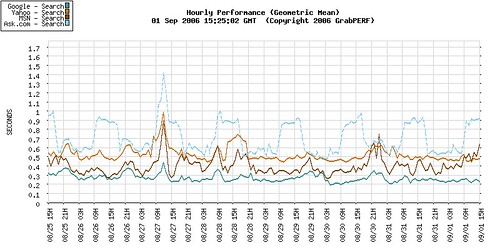

Examining the performance of the same firm within a competitive and comparative context, the predictable baseline performance still appears predictable, but not as good as it could be. The graph shows that most of the other firms in the same vertical, performing the identical search, over the same period of time, and from the same measurement locations, do not show the same daytime pattern of performance degradation.

The context provided by benchmarking now becomes a critical factor. By putting the site side-by-side with other sites delivering the same service, an organization can now question the traditional belief that the site is doing well because we can predict how it will behave.

A simple benchmark such as the one above forces a company to ask hard questions, and should lead to reflection and re-examination of what the predictable baseline really means. A benchmark result should always lead a company to ask if their performance is good enough, and if they want to get better, what will it take.

Benchmarking relies on the idea of a business process. The old approach to benchmarks only considered firms in the narrowly defined scope of the industry verticals; another approach considers company homepages without any context or reliable comparative structure in place to compensate for the differences between pages and sites.

It is not difficult to define a benchmark that allows for the comparison of a major bank to a major retailer, and a major social networking site, and a major online mail provider. By clearly defining a business process that these sites share (in this case let’s take the user-authentication process) you can compare companies across industry verticals.

This cross-discipline comparison is crucial. Your customers do this with your site every single day. They visit your site, and tens, maybe hundreds, of other sites every week. They don’t limit their comparison to sites in the same industry vertical; they perform cross-vertical business process critiques intuitively, and then share these results with others anecdotally.

In many cases, a cross-vertical performance comparison cannot be performed, as there are too many variables and differences to perform a head-to-head speed analysis. Luckily for the Web performance field, speed is only one metric that can be used for comparison. By stretching Web site performance analysis beyond speed, comparing sites with vastly different business processes and industries can be done in a way that treats all sites equally. The decade-long focus on speed and performance has allowed other metrics to be pushed aside.

Having a fast site is good. But that’s not all there is to Web performance. If you were to compare the state of Web performance benchmarking to the car-buying public, the industry has been stuck in the role of a power-hungry, horsepower-obsessed teenage boy for too long. Just as your automobile needs and requirements evolve (ok, maybe this doesn’t apply to everyone), so do your Web performance requirements.